A FACULTY GUIDE TO PHOTOCOPYING

FOR CLASSROOM USE

Robert J. Kasunic, Esquire

INTRODUCTION

The issue of photocopying for

classroom purposes has become a significant concern for faculty members of many

schools and universities. Educators should be aware of the rules governing

photocopying. In particular, they should know when it may be done without the

consent of the copyright owner, how exposure to liability may be reduced, when

and how permission to photocopy should be obtained, and under what circumstances

a university will indemnify an educator against claims of copyright infringement

arising out of photocopying for classroom use.

Educators need to have clear answers to all of these questions. The

present state of copyright law, however, demands more than answers. It requires

that the decision of whether to photocopy copyrighted material for classroom use

be based on a teacher's informed understanding of the subtlety and complexity of

the copyright law and the doctrine of fair use. Many educators believe that

knowledge of copyright law is unnecessary in order to carry out their roles as

teachers. Yet, there are many practical reasons why faculty members should

become informed on the law of copyright, such as damages for infringement,

restrictive university photocopying policies, and restrictive policies by

commercial copy centers.

The

Copyright Act of 1976 1 specifies the exclusive rights of copyright owners and

permits actual or statutory monetary damages when copyrights are infringed.

Actual damages are awarded when the copyright owner proves the direct results

of the infringement. This often includes profits realized by the infringing

party. Statutory damages of up to $ 100,000 may be imposed if the copyright

owner proves that the infringement was committed willfully. Statutory damages,

however, are precluded if the court determines that an employee or agent of a

nonprofit educational institution had reasonable grounds for believing that a

particular use was fair. 2

Educators may underestimate the

likelihood of getting sued for copyright infringement. While the likelihood of

suit may not be great, most university administrations have adopted copyright

policies to limit potential liability for

infringement. These university policies are often more restrictive than

the Copyright Act itself.

Moreover, most commercial copy centers have adopted restrictive photocopying

policies in accordance with copyright law and a recent decision in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New York. 3 As a result of

this decision, a teacher can no longer walk into most commercial copy centers

and ask to have copyrighted material photocopied without first obtaining

permission from the copyright owner or paying for the copy center to obtain

permission.

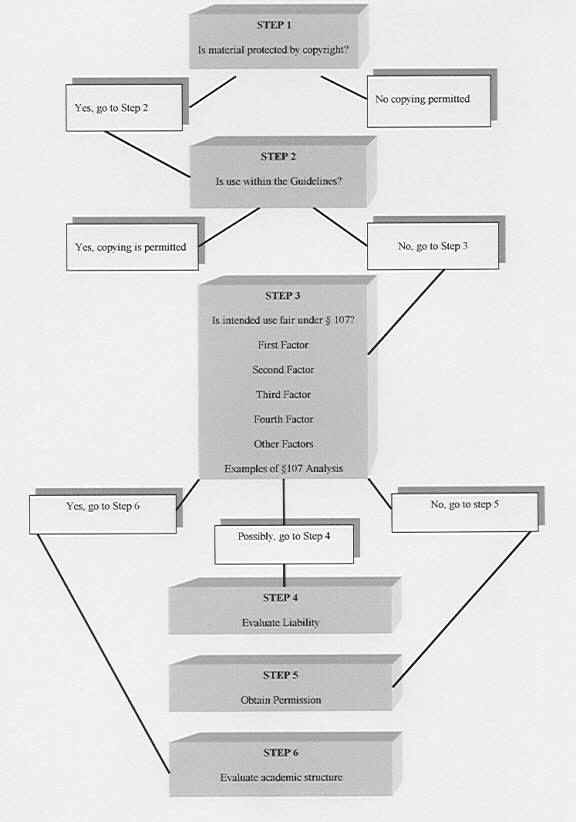

The purpose of this article is to provide educators with a practical step‑by‑step guide to copyright law as it relates to educational photocopying. It will present a logical analysis that educators should follow when faced with the necessity or desire to photocopy material for students. Figure I presents a flow chart of the sequence of the steps followed in this guide.

Step

One. First, determine whether a copyright exists for a given work. This

requires a brief analysis of the material to determine copyright duration and

whether the material has notice of a copyright.

Step

Two. If a copyright exists, then review the "Agreement on Guidelines for

Classroom Copying in Not-for-Profit Educational Institutions with respect to

Books and Periodicals" ("Guidelines"). 4

The Guidelines represent the minimum

standard of the fair use doctrine and, therefore, it is permissible to photocopy

copyrighted material within these guidelines.

Step

Three. If the teacher wants

to photocopy material outside the limits of the Guidelines, a third step in the

analysis is necessary. The educator should examine the intended use of the

material in relation to the purpose of the copyright law and the doctrine of

fair use. An understanding of the doctrine and its four codified factors is

essential for determining whether a particular use is fair.

Step Four. Once an educator understands the fair use doctrine, he must then examine the Copyright Act's damage and excuse provisions to determine the risk of suit for copyright infringement. This fourth step outlines a teacher's options if he is uncertain whether fair use is applicable.

Step

Five. The fifth step examines what

to do if fair use does not apply and explains how to obtain permission to

photocopy material.

Step

Six. The final step in the

analysis considers the academic structure and the process of photocopying and

distributing material to students. The teacher must consider the academic

environment, including whether the teachers, the school, or an outside service

photocopies and/or distributes materials for classroom use.

At first glance, the scope of

this paper seems broader than necessary. Nevertheless, photocopying copyrighted

material beyond the boundaries of the narrow Guidelines requires either

permission or a claim of fair use. Therefore, since permission is usually

difficult and time-consuming to obtain, a Sufficient understanding affair use in

copyright law is an essential tool for an educator. Providing material to

students and updating that material is an important aspect of teaching, and if

the right of fair use is not understood and used by educators, it will be lost.

STEP

ONE: IS THE MATERIAL COPYRIGHTED?

Notices. The

most obvious sign that a work is copyrighted is the presence of either

"Copyright," "Copr.," or "ă"

in addition to the name of the author or copyright owner and the year in which

the work was first published. This copyright notice is usually located in the

front pages of a book or periodical, but the notice may appear in any location

which is reasonably conspicuous. For compilations, such as periodicals or

anthologies, the volume, not each article, requires a copyright notice. Some

journals permit photocopying for certain purposes which are usually explained

near the copyright notice.

Published works which were never copyrighted. Generally, works published before January 1, 1978 without copyright notice are not protected by copyright law because they have entered the "public domain." These publications may be copied without restriction. If the copier is informed by the owner that the material is copyrighted and there is no notice due to an omission, the copyright owner has the right to remedy this defect by informing the copier of the existence of a copyright. No liability attaches until the copier receives notice from the copyright owner.

Published works whose

copyrights have expired. Copyrights on materials in

effect prior to 1916 have expired because the maximum protection available prior

to January 1, 1978 is seventy‑five years. Some material copyrighted after

1917 was initially covered for twenty-eight years and renewable upon

request. Before copying such materials,

either

assume that they are still protected or contact the publisher, author, or U.S.

Copyright Office in Washington, D.C. and inquire as to whether the copyright was

renewed for an additional twenty‑eight years. If fifty-six years had

gone by before September 9, 1962, the material is in the public domain and may

be copied. 5

Government Publications.

Material prepared by the United States Government or by an employee of the

Federal Government within the scope of his official duties are not copyrightable

under §105 and may be copied freely. The U.S. Government may, however, receive

and hold copyrights transferred to it by an assignment or bequest. These

transfers of copyright are indicated by notice.

Some material prepared by state governments may be copied, but it important to

note that states, unlike the U.S. Government, are allowed to copyright works. It

is also important to determine whether the state government is the actual

publisher. In some states, private companies publish the codes and case

reporters, thus acquiring copyrightable elements, such as headnotes or the

selection and arrangement of the material.

Copyrighted Works.

To be cautious, all other publications should be assumed to be copyrighted. In

addition, on March 1, 1989, the United States became a member of the Berne

Convention, and by doing so removed the requirement of copyright notice. All

materials written on or after March 1, 1989 are copyrighted with or without

notice unless the copyright is expressly waived.

Unpublished Works.

Unpublished works have been given special protection by the courts under § 107

of the Copyright Act of 1976, which was recently amended. Unpublished works are

not distributed to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, rental,

lease, or lending. Although unpublished works are protected from the moment of

their creation, the amended § 107 includes the necessity of a fair use analysis

in the copying of unpublished as well as published works. Therefore, before

photocopying unpublished works, teachers must either obtain permission or

perform a fair use analysis. Based on the case law preceding the amendment of

section 107, a teacher should be cautious in photocopying unpublished works

because it is difficult to ascertain its potential market, and this is a

critical factor in a fair use analysis.

STEP

TWO: IS USE WITHIN THE GUIDELINES?

If a work is copyrighted or presumed to be copyrighted, the

next step for a teacher is to determine whether it is within the boundaries of

the Guidelines. The Guidelines were promulgated as an unofficial compromise

between publishers and educational associations. The Guidelines are not the law

and do not set any limits on the teacher's right to copy under fair use. They

are, in fact, a "reasonable interpretation of the minimum standards of fair

use.” 6 As such, they

represent a safe harbor for educators who stay within their scope. Therefore, it

is worth determining whether an intended use of a copyrighted work is within the

boundaries of the Guidelines before embarking upon a more complex fair use

analysis.

Photocopying

which is permitted under the Guidelines in not-for-profit educational

institutions.

1.

Single copies for teachers. Any of the following may be copied for

scholarly research or for classroom purposes, and the property becomes the

property of the user:

a.

a chapter from a book, b. an article from a periodical or newspaper,

c.

a short story, short essay, or short poem whether or not from a collective work,

and

d.

a chart, graph, diagram, drawing, cartoon or picture from a book, periodical or

newspaper.

2.

Multiple copies for classroom use. A teacher may make multiple copies for

a one-time distribution in a class to students when:

a.

no more than one copy for each student is made,

b.

a notice of copyright is written on the first sheet, or a copy of the page on

which the copyright appears is attached,

c.

copied material amounts to only a small proportion of the original work,

d.

selections of poetry, prose or illustrations are sparing (poems of no more than

250 words, prose if the complete article is less than 2500 words, or an excerpt

not to exceed 1000 words or 10% of the work, whichever is less),

e.

the copying is at the instance and inspiration of the individual teacher,

f.

the decision to use the work and its use are so close in time that it would be

unreasonable to expect a timely reply to a request for permission,

g.

the copying is for only one course in the school,

h.

there is no more than one poem, article or essay or two excerpts are copied from

the same author, and no more than three excerpts from the same collective work

or periodical volume during one class term, there are no more than nine

instances of such multiple copying for one course during one term, and J. the

same material is not repeatedly copied.

While it is useful to

determine whether material intended for use is within the Guidelines, the

quantity and frequency limitations are seldom met. For instance, the requirement

that the same material may not be repeatedly copied means that use within the

Guidelines for one semester may be outside the Guidelines if the teacher chooses

to use the same material the following semester. If the material intended for

use is beyond the scope of the Guidelines' safe harbor, then the teacher must go

to the next step in the analysis.

STEP

THREE: IS USE FAIR?

Many

works which faculty members want to photocopy for classroom use are copyrighted.

Most required uses of photocopied material will not meet the tests of brevity,

spontaneity, and cumulative effect of the Guidelines. The teacher is then faced

with four options:

- to

not use the copyrighted material,

- to

require the students to purchase the entire work,

- to

obtain permission to photocopy the material, or

- to determine whether the use is within the maximum limits of fair use.

The first option is

unacceptable if a teacher considers material to be relevant and important for

his students. The purpose of the copyright law is to promote the dissemination

of creative works to the public, not to deter this dissemination. 7 The primary goal of copyright law is to promote progress and

the public interest. Education is the "paramount public interest" and

the most important means of promoting progress.8

The legislative history of the Copyright Act clearly supports this

interest in education.

The second option is

unreasonable if only a portion of a work is to be used. Students cannot afford

to purchase libraries of works in order to utilize parts of each work. The

unreasonableness of such a proposition seems to be a major consideration in the

creation and codification of the fair use doctrine.

The third option is a

valid consideration; permission may, in many cases, be the best alternative.

This option, however, should be utilized only after the fourth option, a fair

use analysis, has proved unhelpful. If the doctrine of fair use applies to the

situation in question, permission is unnecessary. Fair use is a limitation on

the exclusive rights of copyright owners. It protects the primary goal of

copyright law, which is the promotion of progress and public interest.

A more practical reason for

undertaking a fair use analysis before seeking permission is that a request for

permission is a time-consuming process. If permission is denied or the

process is overly burdensome, then the teacher will have spent considerable time

and effort without obtaining the anticipated result. This consumption of time

could have been avoided had the teacher made an independent analysis first.

Therefore, the next appropriate step for a teacher to make is an analysis of

fair use.

Fair use is a means of

balancing the interests of the public with those of the author. The limited

monopoly of copyright was viewed by Congress as the best incentive for the

production and dissemination of creative work to the public. However, rewarding

the copyright owner is a secondary consideration. 9

"The primary objective of copyright is not to reward the labor of

authors but “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and the useful Arts."

10

The courts accomplished

a compromise between society's interest in die use of a copyrighted work and the

interest ofthe

author by means of the common law doctrine of fair use. This doctrine allowed a

copyrighted work to be used in a manner which served the public interest without

the necessity of obtaining the owner's consent.

Congress codified the judge-made

law of fair use in § 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976. It provides:

Notwithstanding

the provisions of § 106, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use

by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by

that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching

(including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not

an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in

any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include--

(1)

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a

commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2)

the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3)

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted

work as a whole; and

(4)

the effect of the use upon the potential market or value of the copyrighted work

(emphasis added). 11

Section 107

specifically identifies teaching, including multiple copies for classroom use,

as a potential fair use. In order to determine whether any particular use is

fair, the four mandatory factors must be considered. Fair use is determined by a

step-by-step evaluation of these factors by the educator. After each factor is

considered, the final decision of fair use should be based on the reasonable and

informed judgment of the teacher.

Factor One -- The

purpose and character of the use. This first

factor in the fair use analysis is paramount because it leads to presumptions.

If the use of a copyrighted work is for commercial purposes, then it is

presumptively an unfair use. On the other hand, if the use is for nonprofit

educational purposes, the use is presumed to be fair. These presumptions may,

however, be altered by the other factors.

The mere assertion of

nonprofit educational status is insufficient. The teacher and the institution he

works for must have no direct or indirect profit motive. At most accredited

schools and universities, the nonprofit educational purpose will be legitimate.

Another consideration is

that any charge for photocopied material must reflect only the actual cost of

photocopying. The use may be categorized as commercial if additional charges

above the actual cost of photocopying are levied. Additional charges could be

viewed as an encroachment on the traditional role of publishers and retailers.

In

addition to the commercial/nonprofit distinction, courts will consider a

productive/nonproductive analysis. To strengthen a presumption of fair use, it

is helpful to make a productive use of the photocopied work. The addition of

original commentary or questions by an educator may persuade a court to consider

a use productive. The court in Basic Books, Inc. v. Kinko's Graphics Corp.

noted that a professor's selection of articles for anthologies may be enough to

constitute a productive use. 12

Factor Two -- The nature of the copyrighted work. This factor focuses on

the type of copyrighted material copied rather than on the intended use. The use

or copying of factual, functional or nonfiction works is more likely to be

viewed as fair use than is the use of fictional works. The reason is that facts

contained in these types of works are considered to be important to the public.

A monopoly of factual information is not the purpose of the copyright law.

Copyright law is a means of encouraging original expression and dissemination of

such information to the public. One cannot monopolize an idea or fact by means

of the copyright law. Factual, functional, and nonfiction works contain less

originality than fictional works and utilize material which others should be

encouraged to build on or re‑interpret.

A finding that a work is factual is only one factor to be considered. Congress did not state what weight should be given to these individual factors. If a use is presumed fair due to the first factor, then a finding that the nature of the copyrighted work is factual adds weight to this presumption. If rebutted, further analysis is necessary.

Factor Three -- The

amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted

work as a whole. The third factor focuses on

the amount of the copyrighted material used. The less of the work that is used,

the more likely that the use is fair.

However, amount is not

solely a quantitative assessment. The Supreme Court has found that a qualitative

assessment is similarly relevant when analyzing this factor. Using a small

portion of a work which represents the "heart" of the work may lead to

a conclusion that this factor weighs against fair use. 13

If the first two factors

lead to a presumption of fair use, this factor becomes less important. The

copying of entire works has been held to be within fair use, yet the copying of

entire works must also be reasonable. For example, even if the first two factors

favor fair use, the copying of an entire book may not be fair use. This is

particularly likely if the entire work is commercially available. On the other

hand, the copying of an entire article, a part of a greater whole, may be fair

use even if it is commercially available. Use of ail entire work for only one

semester is more likely to be considered fair use than is repeated use of that

work. Reasonable judgment and respect for an author's rights must be applied in

analyzing these factors and must be weighed with the necessity for the use.

Factor Four -- The

effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted

work.

In Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, the Supreme

Court found this factor to be the most important consideration. 14 The effect of

the photocopying on the market for the copyrighted material need not be actual.

All that is necessary is that the use will have a substantial effect on the

potential market for the copyrighted material.

The reason that this factor is

so important is that an author would be discouraged from writing for a market

that would not provide compensation. If the potential market for a particular

copyrighted material is the academic community, then the photocopying of this

work would deprive the author or copyright owner of intended income. This would

reduce the incentive to write or publish academic textbooks. If the intended

market is the general public, however, educational photocopying may have only a

minimal effect and this would not be enough to discourage the author.

The economic impact of copying

is an important consideration. The copying of an expensive work may be dangerous

because copying even a portion of it, which constitutes the heart of the work,

could have a substantial economic impact. This is particularly true if the

copying becomes widespread. Even though one instance of such copying by a

teacher may not be considered a substantial hardship, if many teachers copied

the work, the aggregate could have a significant impact on the potential market.

Teachers should be advised to use photocopied material as supplements to texts

rather than replacements for them. This type of use would have less of an effect

on the overall educational market.

If there are adequate incentives, other than financial, to the creation of

material, it may be more likely that use of the work will be considered fair. An

example of this would be the copying of scholarly articles. It could be argued

that the incentive for writing such articles is not money but instead

recognition, prestige, and scholarship. If so, the photocopying of such a work

would be unlikely to decrease the incentive to produce it. Yet, the publisher of

a scholarly journal should be considered. If the publisher is a for profit

business, photocopying may deter the publication of these journals. The economic

incentive of copyrights as a means of encouraging expression must always be

considered in a fair use analysis.

Additional Factor -- Good Faith.

Good faith is essential in any fair use defense. Photocopies of copyrighted

material must always bear notice of copyright; an author always deserves to be

credited for his work. Failure to include notice of copyright may destroy any

claim of fair use, even if all other factors are in favor of such use.

If material contains no

notice of copyright, notice of the identity of the author should be included on

the copies. This at least shows that the educator has considered the owner's

rights in the determination of fair use. Since there is no requirement of notice

of copyright by authors after March 1, 1989, simply providing credit to the

author and the date of the publication would put others on notice that a

copyright may exist.

An

additional element of good faith is involved in the repeated use of copyrighted

material. If specific material is to be used for more than one school term it

becomes harder to argue that it was necessary to copy without prior

authorization. Good faith requires that a teacher use fairness, reasonableness,

and common sense.

. Basic Books, Inc. v.

Kinko's Graphics Corp.,15 is

the most recent decision by a federal district court relevant to the issue of

educational photocopying. 16 In

this case, the plaintiffs, eight publishing companies, brought suit against

Kinko's alleging copyright infringement. Kinko's, a commercial photocopying

center, had copied excerpts from copyrighted books without permission and

compiled them into course packets which it then sold to students. Kinko's

claimed that this was fair use because it was acting as an agent of teachers.

The court rejected the claim of fair use and found copyright infringement. By

applying the fair use factors, the court concluded that Kinko's had infringed

the copyrights of the eight publishers. 17

The first factor was found to weigh against fair use. Kinko's had made

considerable profit from its photocopying for teachers and students. Even though

the copying was eventually used for nonprofit educational purposes, Kinko's use

of the material was not altruistic. Kinko's use was also found to be

unproductive because the copy center added nothing to the works and did not

select the articles used in the anthologies. As a result of this commercial and

unproductive use, the court found a presumption of unfair use.

Kinko's also argued that

it was an agent of a nonprofit educational institution and thus fell under the

exculpatory damage provisions. The court found, however, that Kinko's actively

solicited business from professors and boasted of its expertise in obtaining

copyright permissions. Kinko's was found to be an independent contractor rather

than an agent.

The second factor, the nature of the copyrighted works, weighed in favor of fair

use because all of the works copied were found to be factual.

The third factor, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, went

against Kinko's use. The portions copied were seen as critical parts of the

copyrighted books. Even though the quantitative amounts ranged from only five to

twenty‑eight percent, the qualitative amounts were held to be substantial.

The

final factor also weighed against Kinko's. Kinko's copied and sold nationwide

its packets at much cheaper prices than the originals because its costs were

lower than those of publishers. The purchase of the packets from Kinko's was

found to obviate the purchase of the copyrighted works.

Based on the analysis of the four fair use factors, the court found that Kinko's

use was unfair. The most important factor in this case, however, was Kinko's

commercial purpose. The court found that Kinko's did not play a nonprofit

educational role. Kinko's assistance to nonprofit educators was primarily for

commercial profit.

The major Supreme Court cases addressing fair use are Harper & Row

Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 18

Salinger v. Random House, Inc., 19 and Sony Corp. of Am. v.

Universal City Studios, Inc. 20

Harper & Row

and Salinger were suits for the unauthorized use of unpublished works. In

both instances, there was a finding of copyright infringement. Since unpublished

works are given special protection by the courts, fair use generally will not

apply to unpublished works. 21

In Harper & Row,

the Nation magazine published portions of President Ford's biography prior to

publication of the book. As a result of the prepublication, Time magazine

canceled an agreement for the exclusive rights to print prepublication excerpts.

Thus, the purpose of the use, the first factor, weighed against Nation. Although

the use was to provide news, this article was used for commercial purposes.

The Court found the second factor to be a "critical element;" the

unpublished nature of the copyrighted work tended

to negate a defense of fair use. 22

The next factor, the amount

and substantiality of the portion used, was found to be insubstantial in

quantitative terms but substantial in qualitative terms. The Court stated that

Nation copied what was "essentially the heart of the book." 23

The fourth factor was

identified in Harper & Row as "the single most important element

of fair use.” 24 The cancellation of Time magazine's agreement was found to

present clear evidence of actual damage, which is more than that needed to prove

this factor. All that is necessary to negate fair use is that should the use

become widespread, "it would adversely affect the potential market for the

copyrighted work." 25

The Salinger case

involved a biographer's use of J.D. Salinger's unpublished letters. The

biography was clearly for commercial purposes. The unpublished nature of the

letters weighed against fair use. The amount used was only two hundred words,

but numerous passages closely paraphrased portions of the letters. The court

found that, based on these factors, there was no fair use.

Finally, Sony involved

a suit by a copyright owner of television programs against the manufacturer and

seller of home video tape recorders ("VTRs"). The question posed was

whether the sale of the VTRs to the public infringed the copyright owner's

exclusive rights. The Court answered this question by applying the four fair use

factors. The Court found that the use of VTRs was for noncommercial private home

use. The first factor therefore led to a presumption of fair use. The private

nature of the use was emphasized in the opinion. 26

Analysis

of the nature of the copyrighted work revealed that the copyrighted programs

were initially available to theviewer entirely free of charge and that

videotaping these programs was merely a form of timeshifting .27 The Court

stressed the free nature of the works. The Court also found that copying served

an important service of providing VTR owners the ability to view educational,

religious, and sports broadcasts at a later time. Although the work at issue in

this case was entertainment, the Court was not willing to deprive the public of

the potential educational and informational uses of a VTR. Although the works

were copied in their entirety the Court held that this did not destroy a finding

of fair use. 28

The analysis of the final

factor explained that a noncommercial use of a copyrighted work requires proof

that "some meaningful likelihood of future happen exists" whereas with

commercial use of a copyrighted work that likelihood may be presumed. 29

In this case, the harm was held to be speculative and minimal.

These factual summaries

of important fair use decisions provide an example of how the courts analyze the

fair use factors. A much better understanding would result from reading some

actual decisions because a reasonable understanding of fair use involves

examining how the courts have dealt with various situations.

STEP FOUR: EVALUATE LIABILITY

Remedies available to a party

whose copyright has been infringed are statutory damages, actual damages, and

injunctive relief Statutory damages are penalties for infringement ranging from

$500 to $100,000. Actual damages are the amount of actual harm caused to the

copyright owner, including any profits made by the copyright infringer.

Injunctive relief is a court order requiring an end to present and future

infringement.

If a teacher follows the analysis set out in this guide, a conclusion that

specific copying is fair use will probably be considered a reasonable belief

made in good faith. This is important because statutory damages are not

permitted:

where an infringer believed and had reasonable grounds for believing that his or

her use of the copyrighted work was a fair use under section 107, if the

infringer was: (i) an employee or agent of a nonprofit educational institution,

library, or archives acting within the scope of his or her employment, or such

institution, library, or archives itself, which infringed by reproducing the

work in copies . . .. 30

Congress added this section to

provide teachers with greater certainty. As long as the teacher has reasonable

grounds for believing that a particular use is fair, no statutory damages will

be awarded to a copyright owner even if the use is found to be an infringement.

In these cases, the remaining potential for an injunction or actual damages

would probably not be great enough to cause a chilling effect on fair use by

teachers.

When a particular use is

questionable, there is one factor which must be considered ‑ the cost of

defending a law suit. This potential cost is the greatest source of

administrative restrictiveness on the fair use policy. It is also the major flaw

in the congressional intent to provide teachers with greater certainty. The cost

of defending a copyright infringement suit is often great and causes a chilling

effect on fair use by educators.

When a teacher suspects

a particular use is questionable, it may be beneficial to obtain advice from an

experienced person within the school or from the attorney general's office if it

is a state school. When a particular use reaches the outer limits of fair use,

the general counsel or attorney general's office could become a final arbiter in

the decision of whether a claim of fair use is reasonable.

It is essential that

some procedure is implemented in every academic institution which will allow

teachers to responsibly utilize their right of fair use. When institutional

procedures are inadequate, universities expose themselves to liability and

court‑ordered restrictions. This has the effect of chilling reasonable

fair use by educators. On the other hand, when institutional procedures are

overly restrictive, educators are more apt to simply ignore or bypass a fair use

analysis. This undermines the protections afforded by the law and exposes

individual teachers to potential liability for willful infringement.

The implementation of

reasonable procedures would protect all of the interests involved, including

those of educators, students, academic institutions, copyright owners,

publishers, and the public. Academic policies and procedures which require

teachers to carefully balance these interests and responsibly determine whether

a particular use is fair are the best means of preventing liability and

achieving the goals of the congressional scheme of copyrights.

STEP FIVE: OBTAIN PERMISSION

If it is determined that fair use is not applicable to a particular use, two final options are available, The teacher can obtain permission to copy the material, or he may have a commercial copy center obtain permission and copy the material for him.

To obtain permission to copy,

it is necessary to determine who owns the copyright. This is sometimes difficult

since copyrights may be sold, transferred, licensed, and devised. The author or

the publisher may be contacted to determine who owns the copyright. If the

copyright is registered, the U.S. Copyright Office in the Library of Congress

may possess information on the ownership of the copyright, but finding this

information may be an extremely time-consuming process. 31

Once the educator

determines who owns the copyright, lie must provide the copyright owner with

specific information in order to obtain permission. 32

The Association of American Publishers has said that the following facts

are necessary in order to authorize duplication of copyrighted materials. These

facts are:

1.

title, author and/or editor, and edition of materials to be duplicated;

2.

exact material to be used, giving amount, page numbers, chapters and, if

possible, a photocopy of the material;

3.

number of copies to be made;

4.

use to be made of the duplicated materials (and duration);

5.

form of distribution (classroom, newsletter, etc.);

6.

whether or not the material is to be sold; and

7.

type of reprint (ditto, photography, offset, typeset).

The request should be sent

with a self‑addressed return envelope to the permissions department of the

publisher in question. 33 Permission

often takes considerable time, so lead time is necessary. It is also advisable

to follow up with a written request for permission or with a phone call to the

copyright owner.

For certain

publications, permission may be obtained from the Copyright Clearance Center

("CCC").34 For those publications, the CCC grants permission and

collects fees for photocopying rights. If a publication is registered, this fact

will often appear near the notice of copyright in a publication. Libraries may

also have a list of which publications are registered.

If

a teacher does not have the time or the inclination to obtain permission

individually, commercial copy centers may perform this service for an additional

fee. As a result of the suit against Kinko's, for example, it is now Kinko's

standard operating procedure to obtain permission before photocopying

copyrighted works.

STEP

SIX: EVALUATE ACADEMIC STRUCTURE

The last part of this guide deals with the actual act of photocopying and distribution of photocopied material to students. If a teacher determines that a particular use is fair, the means of photocopying or distribution may have a dramatic impact on the final determination of fair use.

There

are five basic models which a school may use:

1.

the individual teacher copies and distributes to the students;

2.

the school copies at the request of the teacher and the teacher distributes to

the students;

3.

the school copies and distributes to the students at the request of the teacher,

4. tile school copies at the request of the teacher and an outside source

distributes (e.g., a bookstore); and

5.

an outside source copies and distributes (e.g., a commercial copy center).

In any of these situations, if there is no charge beyond the actual cost of photocopying, fair use will be unaffected. This is usually the case in the first three models. Teachers frequently hand out photocopies to their students without charging the students. This is probably the safest method of copying and distribution. Similarly, school reprographic departments often make photocopies, within certain limits, at the request of teachers and then give these copies to the teachers to distribute free of charge. This too would not affect the fair use analysis.

In the third model, the

copying and distribution by the school is usually either free to the students or

the students are charged the actual cost of photocopying. This would not affect

the fair use analysis.

An effect on the fair use

analysis occurs when additional cost is added to the cost of photocopying in the

form of profit. These additional costs are most common in the last two models.

When a school copies and has an outside source distribute the materials, the

outside source is usually a commercial operation such as a bookstore. A

commercial business will usually find it necessary to add a surcharge to the

actual cost of photocopying. The addition of a profit motive in the distribution

process may change the character or nature of the use (the first fair use

factor) from nonprofit to commercial. Thus, the presumption would arise that the

use is unfair. This is a dangerous situation for a school because it changes the

entire fair use analysis. Therefore, teachers must consider the process within

which the school operates. Teachers and administrators would be wise to avoid

situations where additional charges are added to photocopied materials.

The fourth model also

may include two variations. The outside distributor may be an independent

operation, such as a neighborhood bookstore. Under agency law, this type of

distributor would probably be viewed as an independent contractor. An

independent contractor would be responsible for its own actions, and thus any

charges added by this type of distributor would place the book store in a

position of potential liability.

If, on the other hand,

the outside distributor is associated with the school, it may be viewed as an

agent of the nonprofit educational institution. An agent of a nonprofit

educational institution would not be liable for statutory damages if a teacher

had a reasonable belief in fair use.

These subtleties in the

relationship of the outside agency to the school are important if an

infringement action was brought against a particular use, but one conclusion is

certain. Any addition of a profit motive in the fair use chain of events may

alter the character of the use. This change in the character or purpose of the

use may ultimately defeat any claim of fair use.

The final model is also

dangerous because commercial copy centers are in the photocopying business for

profit. Profit is built into the actual cost of photocopying as it is with any

commercial business. In light of the Kinko's decision, fair use is unlikely if

the copy center photocopies and distributes to the students directly.

CONCLUSION

Faculty

members should familiarize themselves with the analysis contained within this

guide. Once these concepts are understood, a teacher will be able to quickly

utilize these steps to independently determine how photocopying for classroom

use may be achieved. The rights of the author and the publisher should always be

considered when photocopying copyrighted material. These rights, however, must

be balanced with the public's interest in education. An informed and reasonable

determination of fairness by teachers will best achieve the ends of the

copyright law.

Fair

use is an essential tool to be used by teachers to promote the public interest

in access to necessary information for students. Educators have an important

responsibility to protect the integrity of fair use and the primary purpose of

the copyright law. If educators do not fulfill this vital role by understanding

and utilizing their privilege of fair use, the statutory benefit will be lost.

APPENDIX A

To

request permission to photocopy copyrighted material, it is necessary to inform

the copyright owner of certain information within the request. The following is

a sample letter to an author or publisher requesting permission to copy:

Permissions

Department Any Book Company 601 West 113th Street New York, N.Y. 10025

Dear

Sir/Madam:

I

would like permission to photocopy the following material for use in my class,

"Advanced Intellectual Property," next semester:

Title:

Trademark Practice, Second Edition

Copyright:

Any Book Co., 1989, 1992

Author:

Max Bradford

Material

to be duplicated: Pages 21‑39

Type

of reprint: Photocopies (sample enclosed)

Number

of copies to be distributed: 35

Distribution:

The copies will be distributed only to students registered for the course listed

above. The students will pay only the cost of the photocopying (or, there will

be no charge to the students).

Use:

These pages will be used as a supplement to the required textbook.

I

have enclosed a self‑addressed, stamped envelope for your convenience in

replying to this request.

Sincerely,

Teacher's name

Endnotes

- 17

U.S.C. §§ 101 et. sec. (1988 & Supp. IV 1992).

- 17

U.S.C. § 504(c)(2) (1988).

- 'Basic

Books, Inc. v. Kinko's Graphics Corp., 75 8 F. Supp. 1522 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

- H.R.

Rep. No. 1476, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. at 54, 68 (1976).

- The

Copyright Office performs copyright searches at a cost of $20 an hour.

Anyone may go to the Copyright Office in person and perform a search in the

office's computer system or in the office records. The Copyright Office is

located in the Library of Congress at 101 Independence Avenue S.E.,

Washington, D. C. 20559 and may be contacted at (202) 707‑3000.

- See

H.R. Rep. No. 1476, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 68‑70 (1976), reprinted in

1976 U.S.C.C.A.N. 5681‑83.

- See

Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991).

- William

F. Patry, The Fair Use Privilege in Copyright Law 225 (1985).

- Mazer

v. Stein, 347 U.S. 201, 219 (1954) (quoting United States v. Paramount

Pictures, 334 U.S. 131, 158 (1947)).

- Feist

Publications, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340 (199 1) (quoting

U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8 cl. 8).

- 17

U.S.C. § 107 (1988 & Supp. IV 1992).

- 758

F. Supp. 1522 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

- Harper

& Row Publishers v. Nation Enter., 471 U.S. 539, 544, 565 (1985)

(quoting Harper & Row Publishers v. Nation Enter., 557 F. Supp. 1067,

1072 (1983)).

- Id.

at 566.

- 758

F. Supp. 1522 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

- See

William Patry, supra, note 8. See also Robert J. Kasunic, Fair Use and the

Educator's Right to Photocopy Copyrighted Material for Classroom Use, 19

J.C. & U1. 271 (1992).

- The

Kinko's court discussed what would constitute a reasonable good faith effort

on the part of Kinko's to educate its employees on the nuances of copyright

law and fair use. The court indicated that a reasonable good faith effort to

inform employees would have consisted of hypothetical situations, a factual

summary of the law, facts of the Harper & Row, Salinger, or Sony cases,

"or any which may illustrate some of the complexities of this

doctrine." This standard is appropriate for providing faculty with a

reasonable understanding of the law. Thus far, this article has satisfied

two of the requirements of the standard. It has presented hypothetical

situations within the analysis of the four factors, and it has presented a

factual summary of the law. In order to fully comply with the standard of a

reasonable good faith effort to inform, it is necessary to include in this

guide an analysis of a few of the important cases.

- 471

U.S. 539 (1985).

- 811

F.2d 90 (2d Cir. 1987), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 890 (1987).

- 464

U.S. 417 (1984).

- There

have been no cases addressing the amendment of section 107, which changes

the per se prohibition against copying unpublished works. Section 107 now

requires the same fair use analysis for unpublished works as it requires for

published works. It is the opinion of the author, however, that these cases

would have had the same result even if the amended section 107 had been in

effect at the time of the decisions.

- 471

U.S. at 563 (quoting Comment 58 St. John's L. Rev., 597, 613 (1984)).

- 471

U.S. at 565 (quoting Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters.,

557 F. Supp. 1067, 1072).

- 471

U.S. at 566.

- Id.

at 568 (emphasis in original). It is also worth noting that there was some

proof of bad faith on the part of Nation. Apparently the prepublication

manuscript had been "borrowed" for a period of time without

permission.

- Sony

Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 442.

- Id.

at 449.

- Id.

at 450.

- Id.

at 45 1.

- 17

U.S.C. § 504(c)(2).

- A

teacher must go to the Copyright Office in Washington, D.C. and personally

search the records on the Office's computer system or request the search to

be done by the Copyright Office, a copyright attorney, or reputable search

firm.

- See

Appendix A for a sample letter for permission.

- If the address of the publisher does not appear at the front of the publication, it may be readily obtained in a publication entitled The Literary Marketplace (for books) or Ulrich's International Periodicals (for periodicals), both published by the R.R. Bowker Company. These publications are available at most libraries.

- The

CCC is located at: 21 Congress Street, Salem, MA 01970 and may be reached by

phone at (508) 744-3350.

Copyright © 1993 University of Baltimore School of Law. All Rights Reserved.